Students walk the grounds of Noh Bo Academy, located near the Myanmar border. Text written by a student at Noh Bo Academy: “I feel deeply sad. All our dreams have been lost. I wish the children in the country’s IDP camps could study peacefully and properly. Instead of just feeling sad like us, they live in constant fear. My heart aches every time I think about my country, Myanmar.”

At the end of the school day, a young girl at White School in Mae Sot carefully packs away her pencils. Text written by a teacher at White School: “Because of Myanmar political situation many people face difficulties and many problems. Since military coup some states cut off the electric and the whole country cut off the Internet. So Myanmar people face the difficulties. Please help my country.”

Young girls from Sunshine School sit outside their classroom, laughing together during break-time.

Sunshine School sits on the edge of the Thai-Myanmar border, with the mountains of Myanmar visible in the distance. Every day, new families arrive, hoping to secure a place for their children. Text written by a student at Sunshine School: “I feel sad. The certain future we once had is gone. My country may not survive much longer — it could fall under the control of others.”

Mae-La refugee camp, one of the largest in Southeast Asia, is home to an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people. Text written by a student at KKB School: “Myanmar has faced military coup. Some students cannot attend school. A lot of citizens have no home. Some families don’t meet anymore with their family.”

Sixteen-year-old Nan Yadanar San (bottom right) poses with her football team on the grounds of KKB School, where they live and study. She fled Myanmar alone after fighting reached her village in Karen State, leaving the care of her grandmother to continue her education in Mae Sot. Today, her team competes in local football tournaments alongside Thai and migrant students.

A view of the Mae Sot countryside on a road coming from the north towards Mae Sot city centre. (Text) A student writes: “I’m feeling deeply unhappy every moment. The younger generation is losing their future because of political turmoil, and many people are lost, not knowing what to do. Some are far from home and family, forced to flee due to the unrest. It breaks my heart to be away from my country, living in another place filled with challenges and hardships. This is the weight of what I’m feeling.”

Nan Hser Tha Mote, 28, leads children through a dance rehearsal for the school’s summer camp talent show. A refugee from Karen State, she arrived in Mae Sot in 2015 and began studying at a migrant school. After completing high school, she trained as a teacher and now works with displaced children, helping them rebuild their futures.

Teachers, students, and local villagers gather to watch a summer sports tournament at Maw Kwee School. Located in a rural area near Tha Song Yang, close to the Thai-Myanmar border, the school has become a central hub for the surrounding community of migrants and refugees.

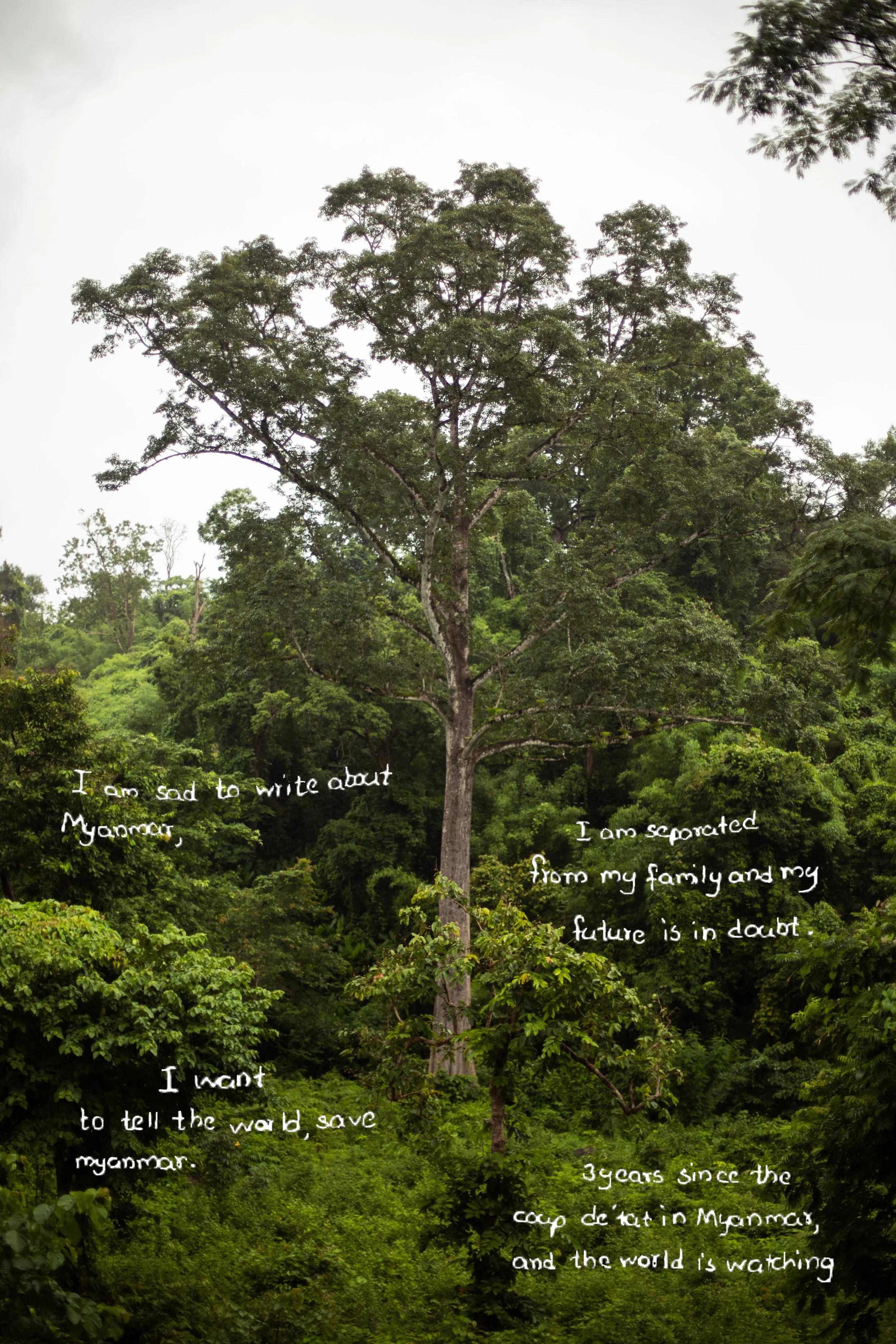

Text written by a migrant teacher from KKB School: “I am sad to write about Myanmar. I am separated from my family and my future is in doubt. I want to tell the world ‘save Myanmar’. 3 years since the coup d’etat in Myanmar and the world is watching.”

Mindscapes of Mae Sot (2024)

The conflict in Myanmar has displaced more than three million civilians, according to the United Nations. For nearly 4 decades, children have fled the country’s political instability and violence in search of safety and education in neighbouring Thailand. In Mae Sot, just across the Thai-Myanmar border, refugee-led schools and NGO-supported learning centres have become sanctuaries where displaced children can learn, play, and rebuild a sense of normality.

I travelled to Mae Sot last year while on assignment for the NGO Givology to document life inside these schools. As a visual journalist, I was struck by a challenging contradiction: while hearing stories of trauma, displacement, and loss, I was photographing scenes of playful, resilient children and tight-knit, hopeful communities. These schools are places of relative safety, but the memories of conflict remain just beneath the surface.

To reflect this dual reality, I invited teachers and students to handwrite their thoughts, memories, and hopes directly onto images of the schools and landscapes. Their testimonies — intimate and unfiltered — transform the photographs into a layered narrative of trauma and survival.